BY PAIGE MAHONEY

Born from the waters of the Ganges Delta in India, cholera has been intertwined with human history for millennia. Early Indian and Greek texts give some insight into when the disease first reared its ugly head, but it was not until the 19th century that cholera gained its reputation as a killer of millions.1 In the 1800s, taking advantage of poor sanitation, overcrowding, and the global travel embraced by Western empires, the bacterium gained a foothold in Europe and North America, triggering its newfound penchant for causing pandemics.

Cholera’s big break came in the 1850s during a London outbreak that killed over 10,000 people.2 Physician John Snow, who witnessed this devastation firsthand, set out to discover why so many people were getting sick. Through careful surveillance, he was able to track the origin of the outbreak to a contaminated water pump on Broad Street in London.2 In what is widely cited as the origin story of modern epidemiology, Snow convinced local authorities to remove the pump’s handle and the outbreak fizzled out.

John Snow’s map that he used to pinpoint the location of London’s 1854 cholera outbreak to a water pump on Broad Street. (link)

Once people figured out the link between contaminated water and cholera, as well as the identity of the bacteria causing the disease, Vibrio cholerae, cholera outbreaks became easier to control.3 At least, that was the case in parts of the world with access to water, sanitation, and hygiene infrastructure, or WaSH.3 For many of us living in the United States, cholera may seem like a problem of the past, but that is not the case for millions around the globe.

Cholera flourishes in places experiencing instability, so it is primed to cause epidemics during humanitarian crises. The overcrowded conditions and destruction of sewage infrastructure associated with these situations benefit a waterborne disease that thrives off of close contact and lack of access to sanitation.4 Treatment for cholera consists of oral or IV rehydration and, if needed, antibiotics, but without access to these resources, mortality rates are around 50% due to complications associated with severe diarrhea.4

The latest yearly data on the global disease burden of cholera comes from 2015, when the disease caused approximately 1.3-1.4 million cases and anywhere from 21,000 to 143,000 deaths.5 More recent data from the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that between January 1st and August 25th, 2025, there were 409,222 cases of cholera and 4738 deaths worldwide.3 Most of these cases were concentrated in the WHO’s Eastern Mediterranean Region and Africa. However, the WHO notes that these numbers are likely underestimates. Given that so many cases happen in the context of war or other humanitarian crises, which reduce access to healthcare and reporting resources, it is hard to account for every single one.

Recent cholera outbreaks have proved the relationship between the disease and crisis: major spikes in incidence were observed during the civil war in South Sudan in the 2010s, after natural disasters in Madagascar, and after the 2010 earthquake in Haiti.3 In this last instance, the outbreak, which was the first time cholera had been observed in Haiti, was attributed to the presence of foreign UN peacekeepers who were there to stabilize the country.6 The Haitian outbreak was further exacerbated by the earthquake’s destruction of WaSH infrastructure.

According to the WHO, Yemen currently has the largest cholera burden in the world; however, civil war in Sudan has meant that Sudan has seen a massive increase in cases in the last two years.3 Yemen’s massive outbreak also began as a result of civil war and caused previously unimaginable numbers of cases. Given these similarities with the Sudanese outbreak, examining strategies deployed in Yemen is a useful way to determine a path forward for Sudan, which is currently experiencing what some have called the world’s largest humanitarian crisis.7

Interestingly, at the peak of the cholera outbreak in Yemen in 2017, the UN also called that situation the world’s worst humanitarian crisis, making this disaster an apt model for what we are seeing in Sudan right now, with some important differences, of course.8

Yemen’s economic circumstances made the country especially vulnerable to a devastating cholera outbreak. Prior to the outbreak of the civil war, it was already one of the poorest countries in the Middle East, with half of the population living in poverty.4 The country’s water supply is completely dependent on ground and rain water, which is not well managed, so water scarcity was an issue even before war-related infrastructure destruction.4 To this point, the Global Alliance Against Cholera has reported that only “55% of rural populations and 79% of urban populations have access to at least basic water sources,” while 30% of people in rural areas defecate in the open, which significantly raises the risk of water contamination.10 This lack of water also worsens food insecurity, and malnutrition is another risk factor for the development of severe cholera. Yemen thus does not have the robust infrastructure necessary to prevent cholera outbreaks during a humanitarian crisis—a pattern that plays out across the world, including in Sudan.

Early on in Yemen’s civil war, observers noted that Saudi Arabian forces seemed to be interfering in the conflict. Yemen’s location on the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden has meant that it has long been a target for global powers looking to expand their reach, and this civil war was no different; Saudi Arabia targeted health and water infrastructure in a strategy the executive director of UNICEF called “a breach of the basic laws of war.”9,11 Retrospective studies would estimate that due to attacks by Saudi forces, only 45% of the country’s health facilities were left functioning, and in 2017, the Lancet estimated that 14.5 million people, or half of Yemen’s population, did not have access to clean water.9,12 Thus, with already scarce WaSH infrastructure being targeted in the fighting, Yemen’s civilians were living in conditions primed for a cholera outbreak—and one soon erupted.

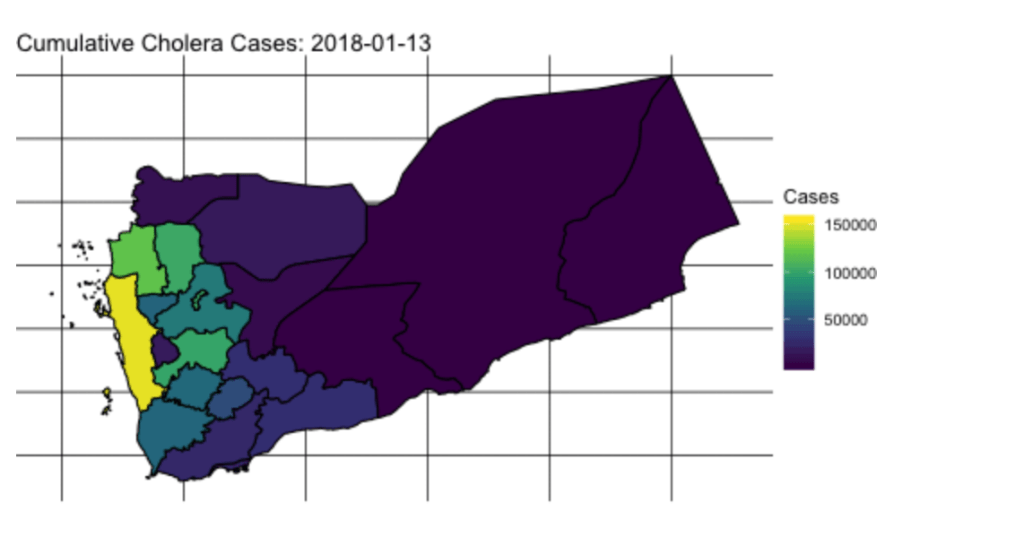

By 2018, the flurry of cholera cases in Yemen was the largest outbreak caused by any disease in recorded epidemiological history.9 Within the first eight months, there were over 2,000 confirmed cholera-related deaths—a staggering figure considering that the disease can be treated.9 As of 2021, there were 2.5 million cases associated with the conflict.4

The response to the Yemen cholera epidemic has been widely criticized in the years since. Even before the first cases appeared in 2016, the world had a cheap, highly effective oral cholera vaccine that could be distributed without trained healthcare workers.13 And yet, the first vaccines were delivered 16 months after the outbreak began, in late 2018.13 Notably, this campaign took place three-and-a-half years after civil war broke out, and even longer after the first signs of conflict appeared, despite the long-recognized link between cholera and war. The question, then, is not why Yemen was struck with the disease, but why the world waited so long to act.

The answer is largely related to money—in 2018, only 47% of the United Nations’ 2016 response plan for the epidemic was funded.13 In 2015, the WHO reported a funding gap of more than 80% related to their efforts in Yemen, while the UN fell short of its requisite funds to prevent a “full blown humanitarian catastrophe” by $1 billion USD.13 When it first became apparent that Yemen was on the verge of a humanitarian crisis, world leaders pledged funds, but as the media attention faded away, so too did the money. The crisis, however, remained.

Demonstrators in London protest the UK’s sale of arms to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates in the context of the Saudi bombings during Yemen’s civil war. (link)

Given this lack of funds and concerns about the feasibility of vaccinating a population that was largely displaced, many organizations thus focused on rebuilding infrastructure. Ultimately, proper water and sanitation strategies are required to prevent cholera outbreaks, but these interventions take time. Prioritizing a vaccination campaign earlier on in the outbreak could have disrupted the spread of disease just enough to ward off a crisis of such magnitude, even though it would not have solved the underlying infrastructure problems.

In May of 2018, UNICEF ran a vaccination campaign that reached 270,000 people, many of whom lived in cholera hot spots.14 This effort and others provided enough protection against the disease for it to decline dramatically in incidence, although the outbreak continued for several more years, with most sources placing the official end between 2021 and 2022.14

The city of El Fasher, located in the western part of Sudan, has been under siege since May 2024.15 Barricaded by paramilitary forces, it is impossible to get aid in or sick people out. Nightly air strikes mean civilians spend hours sheltering in hand-dug trenches, which flood during the rainy season. El Fasher is on the brink of famine. The remaining 260,000 civilians rely on 4 communal kitchens, which are themselves frequent targets of the incessant shellings.15 As a result, people have started eating peanut shell residue mixed with water, which is usually used as livestock feed and is nowhere near enough to sustain the people trapped in El Fasher.

Amidst this chaos, the only thing that has managed to slip into the city is cholera. The disease runs rampant in the crowded conditions, taking advantage of a severely malnourished population that cannot fight it off. It thrives in the flooded trenches and is spurred on by the destruction of practically all sanitation facilities. It is hard to quantify cholera’s impact on El Fasher due to the city’s isolation, but the reports that have made it out from behind the barricade paint a devastating picture.15

In Darfur, the region where El Fasher is located, the WHO has distributed 1.86 million doses of the oral cholera vaccine, while Médecins Sans Frontières workers have initiated education campaigns that focus on hygiene practices and how to find safe drinking water.16,17 These efforts are helpful, but unless they are scaled up and introduced to the areas most in need of help, such as El Fasher, which remains effectively unreachable, cholera will continue to tear through the country.

Alarmingly, disease does not care about international borders. As refugees flee Sudan, cholera has spread to neighboring countries, including Chad, South Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.3 Thus, without intervention, the situation has the potential to become significantly worse for the region, overwhelming other nations with already overburdened healthcare systems due to the influx of refugees and a persistent lack of resources.

There are numerous parallels between the outbreak in Yemen and the current situation in Sudan. First, both started during a civil war, which caused destruction of WaSH infrastructure, population displacement and crowding, and greater food insecurity. Currently, ten million people are estimated to be displaced in Sudan, while half of the population lacks adequate food supplies.7 70% of hospitals in conflict-affected areas of Sudan are non-functional, while hospitals in other regions of the country are overwhelmed by refugees.17 Additionally, both conflicts were or have been prolonged by foreign involvement; in the case of Sudan, there is evidence that the United Arab Emirates have been illegally smuggling weapons to the paramilitary forces fighting against the Sudanese government.15 Finally, neither crisis has gotten the media attention they warrant given their scale. As Yemen’s cholera epidemic showed, without widespread awareness, it is hard to get enough support, both monetary and symbolic, for adequate humanitarian aid.

A map showing the distribution of cholera cases in Yemen at the beginning of 2018 (link)

Cholera has a storied history, from its early origins to its contribution to the field of epidemiology to its association with humanitarian crises today. Each time the disease reappears, it threatens some of the world’s most vulnerable populations’ right to health, and it is the global health community’s responsibility to respond to that crisis. After witnessing the mass destruction caused in Yemen, we have so much more information about how this disease rips through an already stressed population and what works in our fight against it. Now, we have to use that knowledge for good. It is by looking to the past that we will be able to stop the same terrible story from playing out again and again.

——————————

References

- History.com. Cholera. HISTORY https://www.history.com/articles/history-of-cholera (2017).

- Emanuel, G. An ancient disease makes yet another comeback. NPR (2025).

- Cholera – Multi-country with a focus on countries experiencing current surges. World Health Organization https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2025-DON579 (2025).

- Tarnas, M. C., Al-Dheeb, N., Zaman, M. H. & Parker, D. M. Association between air raids and reported incidence of cholera in Yemen, 2016–19: an ecological modelling study. The Lancet Global Health 11, e1955–e1963 (2023).

- Ali, M., Nelson, A. R., Lopez, A. L. & Sack, D. A. Updated global burden of cholera in endemic countries. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9, e0003832 (2015).

- Piarroux, R. & Frerichs, R. R. Cholera and blame in Haiti. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 15, 1380–1381 (2015).

- Sudan faces worst cholera outbreak in years as war devastates infrastructure | International Committee of the Red Cross. https://www.icrc.org/en/article/sudan-faces-worst-cholera-outbreak-years-war-devastates-infrastructure(2025).

- In Focus: Yemen. UN News. https://news.un.org/en/focus/yemen (2018).

- Blackburn, C. C., Lenze, P. E. & Casey, R. P. Conflict and Cholera: Yemen’s Man-Made Public Health Crisis and the Global Implications of Weaponizing Health. Health Security 18, 125–131 (2020).

- Continued cholera epidemic in Yemen. The Global Alliance Against Cholera (G.A.A.C) https://www.choleraalliance.org/en/news/continued-cholera-epidemic-yemen (2021).

- Yemen: Attacks on water facilities, civilian infrastructure, breach ‘basic laws of war’ says UNICEF | UN News. https://news.un.org/en/story/2018/08/1016072 (2018).

- The Lancet. Yemen and cholera: a modern humanity test. The Lancet 390, 626 (2017).

- Federspiel, F. & Ali, M. The cholera outbreak in Yemen: lessons learned and way forward. BMC Public Health 18, 1338 (2018).

- Yemen’s first-ever cholera vaccination campaign | UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/stories/yemens-first-ever-cholera-vaccination-campaign.

- Majdoub, S. ‘A donkey cart out of El Fasher costs more than a new car’: how 500 days under siege is tearing the city apart. The Guardian (2025).

- WHO EMRO – Cholera vaccination campaign launched in Darfur to protect over 1.8 million people. https://www.emro.who.int/sdn/sudan-news/cholera-vaccination-campaign-launched-in-darfur-to-protect-over-1-8-million-people.html.

- Boisson-Walsh, A. Cholera in Sudan amid war and health system collapse. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 24, e681 (2024).