BY CRISTINA GARCIA

A clinician in a crowded ward turns away from the laptop. An AI scribe listens to the conversation between a physician and patient, drafts the notes of the checkup, and files orders for review. Clinicians are able to, as a result, give their undivided attention to the patient and not be distracted by typing notes on the keyboard.1 In many aspects, AI undeniably provides an incredible, meaningful improvement in both workflow and quality of care.

Yet, what if that same AI scribe that permits a physician to look up from the keyboard misunderstands the patient due to them having a distinct English accent? Without a doctor there to verify, an AI scribe that unintentionally documents false symptoms can steer a patient toward the wrong treatment. If that same AI now is acting as a language translator between a physician and a patient, one dropped negation as a result of misinterpreting the patient can flip a ‘no’ symptom into a ‘yes’ symptom. If the doctor does not know the patient’s language, they have no way to catch the mistake. The question, therefore, is not whether AI should be used in healthcare, but how it can be governed in a way that protects patient rights, preserves trust, and advances health equity. Can failure in AI systems be caught and explained before patients feel it? How might these tools alter the interactions between patients and physicians? Are certain groups at an advantage compared to other groups when it comes to using AI?

By international standards, the United Nations’ “right to health” set out in the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) clarified in General Comment No. 14 that everyone is owed the highest attainable standard of health.2 Human rights are universal and apply to all people, regardless of race, color, sex, language, religion, political opinion, national or social origin, property, birth, disability, or any other status.3 That right creates legal duties for governments to pass and enforce policies that ensure universal access to care and tackle the roots of health inequity, including poverty, stigma, and discrimination.

In practice, services must be accessible, acceptable, and of good quality.4 Services must be sufficient in quantity, must be considerate of the ethnicity of individuals, and must ensure patients’ privacy is upheld. The implementation of AI in healthcare systems will require thought on how to ensure it fits within the framework, especially considering concerns over unintentional discrimination and bias in AI algorithms. For example, if an AI scribe can interpret Midwestern English but struggles with Spanish or regional language dialects, that creates an accessibility barrier for patients.

The input of sensitive medical information into algorithms also creates a privacy problem in ensuring that patients’ healthcare information remains secure. Under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), healthcare providers are required to allow necessary access to information while “protecting the privacy of people who seek care and healing.”5 Integrating AI tools into clinical workflows introduces new questions about how securely patient data is stored, transmitted, and used.

Transformative Potential of AI in Healthcare

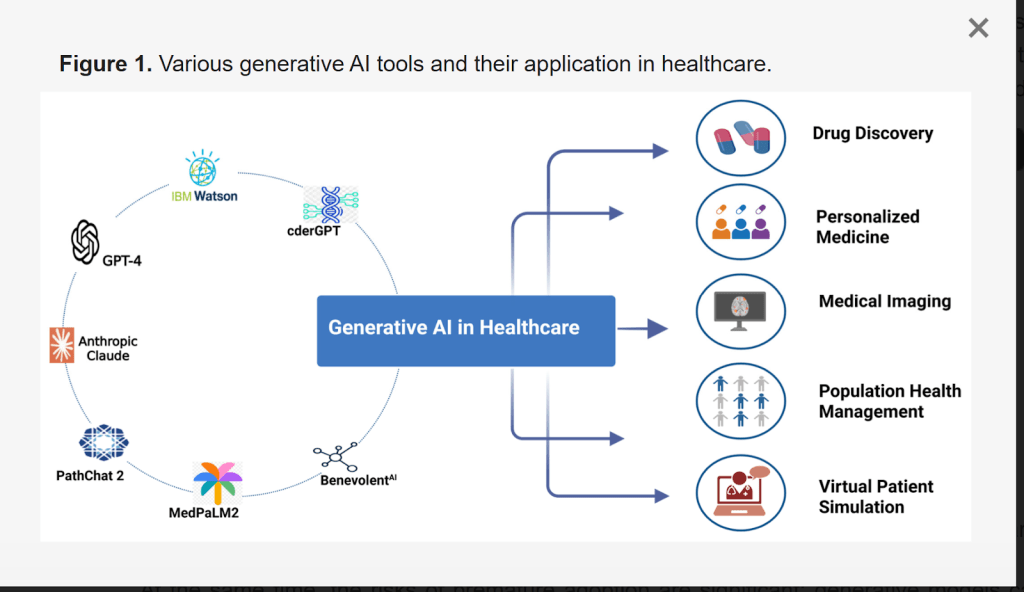

There is little doubt about AI’s revolutionary potential in healthcare, as it is already reshaping how diseases are identified, treated, and prevented. By using machine learning and predictive analytics, AI can process enormous amounts of medical information from scans and genetic data to patient records and identify complex patterns that support earlier diagnosis and more effective clinical intervention.6 In many cases, AI systems perform at or above the level of human clinicians, detecting diseases more quickly and reliably. Beyond diagnosis, AI supports personalized medicine by assisting doctors in tailoring treatments to each patient, improving results while reducing harmful side effects. It also improves the everyday operation of healthcare systems through virtual assistants that help manage scheduling, communication, and documentation, making clinical work more efficient and easing the administrative burden on medical staff.6 Overall, AI represents a major advancement in healthcare, but its success also depends on responsible deployment. The aim of the following sections is to examine key considerations in AI deployment to ensure that its vast potential is achieved through careful, ethical, and patient-centered implementation.

[7] Landscape of generative AI tools and their roles in modern healthcare. Foundation models support a variety of health-related issues, including drug discovery, personalized medicine, medical imaging, population-level analysis, and virtual patient simulation.

How Algorithms Could Reproduce Racial Disparities in Care

A major concern is that AI systems can reinforce existing biases and exacerbate inequities in healthcare. Since these tools learn from historical data, any skew in that data can be learned and reproduced at scale. Datasets that overrepresent certain races, genders, ages, languages, or geographies, and underrepresent others, tend to yield uneven accuracy across patients [8]. A striking example comes from a commercial risk-prediction algorithm used by U.S. hospitals to identify patients who needed extra care.

The 2019 Science study by Obermeyer found that the algorithm systematically underestimated the health needs of Black patients because it used medical expenditure rather than the severity of the condition as the basis for prediction.9 Unfortunately, this metric is unreliable because healthcare spending does not necessarily reflect medical need. Patients who face barriers to accessing care often spend less on healthcare despite having conditions just as urgent as those who receive more services.9 In practice, the software scored Black patients as lower risk than equally ill white patients, because Black patients have historically received less or lower-cost care for the same conditions. As a result, far fewer Black patients were referred to high-need care programs, even when their health status warranted additional support.9 When researchers re-adjusted the model based on actual health needs (based on metrics like lab values, diagnoses, and complications) instead of future spending, the share of Black patients flagged near the eligibility cutoff jumped from about 17.7% to roughly 46.5%.9 A difference like this shows the importance of really understanding what information is guiding the decision-making process of AI collectively.

The Dangers of Unexplainable AI (Transparency Issue)

Another growing worry with medical AI is the “black box” problem, where algorithms give answers without showing how they arrived at them. In other words, the system provides an output, but no one can really see the reasoning behind it.10 AI’s automation can become risky if physicians slowly begin not training themselves anymore to make diagnoses independently, and instead rely too heavily on AI systems. Over time, this could mean doctors begin trusting AI automatically, even when it is wrong, simply because the machine appears confident. When neither doctors, patients, nor even the developers can fully explain how an algorithm reached a conclusion, trust in the healthcare system begins to break down. If AI fails to detect a disease and clinicians cannot recognize the error, patients may suffer serious harm.

It is important to acknowledge that the fear of automation diminishing human skill is not unique to AI but is rather a common concern within technological progress as a whole. A familiar example is the transition from paper maps to GPS systems. People once had to learn how to read maps and develop a strong sense of direction. Now, with Google Maps, many simply follow instructions without the need to fully understand where they are or how they got there. Over time, the navigational skill of map reading and determining by ourselves how to get “unlost” without our phones faded because we no longer need to use those skills. However, in medicine, it could mean something much more serious because human lives are at stake. The uncertainty creates real burdens and stress for patients and families.

[11] Black-box AI gives answers without showing how it got there. The only aspect that matters is the output, which could be problematic from a medical standpoint if patients want to know how and if a deep learning model identifies a diagnosis correctly.

Patient Privacy in the Age of Medical AI

There is further concern surrounding the large volumes of private medical data required to train AI systems. Compared to the data exchanges involved in telemedicine, artificial intelligence applications depend on far greater quantities of patient information, making data security even more critical, especially due to the limited regulation and lack of clear precedent governing who may access patient information and how it should be protected [12].

In practice, this means that the more information AI systems collect, store, and exchange, the greater the risk that sensitive details can be exposed, misused, or stolen, especially as data is often uploaded to cloud servers or processed on external Graphics Processing Units (GPUs), adding additional points where compromise may occur. Many may assume that once personal data is “anonymized,” it becomes completely safe. In reality, that is often not true.12

In a 2018 analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) physical-activity data, researchers showed that even when names and obvious identifiers were removed, people could still be matched back to their health records using only small pieces of publicly available outside information, such as age or location. The procedure achieved re-identification rates of 85.6% for adults and 69.8% for children.12 This demonstrates that removing names alone does not guarantee privacy when datasets are large and detailed. The more information that exists about a person, the easier it becomes to connect the dots and uncover their identity. This highlights the importance of imposing AI regulations to minimize reidentification risks.

Data Labor in AI Development

Behind the appearance of automation, Artificial Intelligence systems that summarize medical notes, flag X-rays, or power diagnostic tools rely on large groups of workers who label images, transcribe audio, and clean data so that algorithms can learn. Demand for this work has grown rapidly as AI has expanded.

In parts of Africa and Southeast Asia, workers have described working 12 to 20-hour days and completing thousands of tasks per shift.13 Pay is often unstable, contracts are unclear, and mental health support is rare, despite the fact that some workers are exposed to disturbing or graphic content as part of their jobs. For example, studies by Oxford University’s Fairwork project have found that major digital labor platforms frequently fail to meet even basic standards for fair wages, safe working conditions, and worker representation.14 Additionally, a 2025 field survey conducted in Colombia, Ghana, and Kenya found many cases of severe anxiety, depression, panic attacks, and symptoms similar to PTSD, alongside widespread reports of unpaid wages or pay being reduced without explanation.14 Recognizing data workers as part of the healthcare ecosystem is essential to ensuring that AI-driven care is truly ethical and sustainable.

Possible Solutions & Final Thoughts

Although AI has much potential in accelerating the pace of healthcare discovery (speeding up drug development, predictive modelling, etc) the excitement should not overshadow the risks. Potential ways to ensure AI systems are implemented in a nondiscriminatory way include evaluating the system for calibration, error parity, and subgroup performance (including race/ethnicity, age, sex, language, disability) before rollout.15 Additionally, to increase transparency, before any hospital introduces an AI tool, community panels composed of patients, bedside clinicians, and public health voices could review plain-language “model cards” that explain how the system works, where its data originates, where it struggles, and how it will be monitored over time.15 These conversations can serve to open the door for patients and clinicians to see AI as a partner in care. Local pilot programs can bring the technology into real clinical settings, where it can prove its value slowly and responsibly, earning trust one decision at a time.

Feedback in these early stages allows systems to mature alongside the people who use them, shaping tools that respond to human needs. In addition, performance data should be openly shared, and systems retrained, especially for high-risk populations, so improvement remains continuous.15 Ultimately, AI may power modern medicine, but it is people, not machines, that power its purpose and breathe meaning into technology. If done right with accountability, AI holds the potential to build a world where fewer people suffer in silence, more lives are saved, and future generations do not just inherit better tools but better care.

https://www.pexels.com/photo/robot-pointing-on-a-wall-8386440/

——————————

References

- DeepScribe. The rise of artificial intelligence in medical transcription. https://www.deepscribe.ai/resources/the-rise-of-artificial-intelligence-in-medical-transcription.

- Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. General comment No. 14: The right to the highest attainable standard of health (Art. 12), E/C.12/2000/4 (United Nations, 2000). https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Women/WRGS/Health/GC14.pdf/

- United Nations. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-right.

- UNICEF. Availability, accessibility, acceptability and quality (AAAQ) framework (2019). https://gbvguidelines.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/AAAQ-framework-Nov-2019-WEB.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). Public Health (10 Sep 2024). https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/php/resources/health-insurance-portability-and-accountability-act-of-1996-hipaa.html

- Faiyazuddin, M. et al. The impact of artificial intelligence on healthcare: a comprehensive review of advancements in diagnostics, treatment, and operational efficiency. Health Sci. Rep. 8, e70312 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.70312

- Rabbani, S. A., El-Tanani, M., Sharma, S., Rabbani, S. S., El-Tanani, Y., Kumar, R. & Saini, M. Generative artificial intelligence in healthcare: applications, implementation challenges and future directions. BioMedInformatics 5, 37 (2025). https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedinformatics5030037

- Business for Social Responsibility (BSR). AI and human rights in healthcare (2023). https://www.bsr.org/reports/BSR-AI-Human-Rights-Healthcare.pdf

- Obermeyer, Z., Powers, B., Vogeli, C. & Mullainathan, S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science 366, 447–453 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax2342

- Regunath, G. Explainability AI. Advancing Analytics (2021). https://www.advancinganalytics.co.uk/blog/2021/7/14/shap

- Xu, H. & Shuttleworth, K. M. J. Medical artificial intelligence and the black box problem: a view based on the ethical principle of “do no harm”. Intell. Med. 3, 100091 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imed.2023.08.001

- Yadav, N. et al. Data privacy in healthcare: in the era of artificial intelligence. Cureus 15, e48606 (2023). PMCID: PMC10718098. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 4224816 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/4224816.

- Du, M. & Okolo, C. T. Reimagining the future of data and AI labor in the Global South (Brookings Institution, 2025). https://www.brookings.edu/articles/reimagining-the-future-of-data-and-ai-labor-in-the-global-south/

- The Guardian. Meet Mercy and Anita – the African workers driving the AI revolution, for just over a dollar an hour (6 July 2024). https://www.theguardian.com/technology/article/2024/jul/06/mercy-anita-african-workers-ai-artificial-intelligence-exploitation-feeding-machine

- European Union. General Data Protection Regulation, Article 12: Transparent information, communication and modalities for the exercise of the rights of the data subject.https://gdpr-info.eu/art-12-gdpr/.