BY ABDUR RAHMAN-OLADOJA

Across much of sub-Saharan Africa, prostate cancer unfolds quietly, away from the urgency and visibility that other global health crises often command. It is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in African men, yet among the least resourced. This disparity reflects not only infrastructural shortcomings but also systemic neglect—an imbalance that exposes the unfulfilled promise of the human right to health.

Prostate cancer has become a defining challenge in Africa’s shifting health landscape. In 2020, it was the most commonly diagnosed cancer among men in 40 of the 48 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, with incidence and mortality rates continuing to rise dramatically across the region. Although African ancestry is a well-established risk factor for aggressive prostate cancer, genetic susceptibility alone does not explain the crisis. Even as global data suggests declining mortality in high-income nations due to early detection and advanced therapy, the opposite trend is evident in sub-Saharan Africa.1

A systematic estimate placed the incidence of prostate cancer in Africa at approximately 21.95 per 100,000 men, with large regional variability and limited registries.2 Recent registry data show that prostate cancer incidence is increasing significantly across sub-Saharan Africa, with annual percentage increases of up to 5% in Harare and nearly 10% in places like Seychelles and Eastern Cape, South Africa.3 Yet despite this growing burden, survival remains alarmingly poor. A multi-country population-based study across ten sub-Saharan African nations found that 76% of men were diagnosed at advanced stages (Stage III or IV), and five-year relative survival averaged just 60%, markedly lower than the survival rates for early-stage disease commonly seen in high-income countries.4

These statistics expose the systemic inequities that make early diagnosis and treatment rare. In many African nations, screening programs are virtually non-existent, pathology capacity is underdeveloped, and oncology resources remain concentrated in a handful of urban centers.

Infrastructure, Access, and the Cost of Delay

Healthcare in Africa has historically been structured to address infectious disease outbreaks, like HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, instead of long-term, resource-intensive conditions like prostate cancer. This mismatch, though understandable from a historical standpoint, has left cancer care infrastructure chronically underdeveloped. Across the continent, radiotherapy infrastructure remains critically limited: as of 2010, only 23 of 52 African countries had any external beam radiotherapy, and more than half of all machines were concentrated in just two nations.5

Even where facilities do exist, access is restricted by distance, cost, and waiting times. A 2024 systematic review documented that African patients face “geographic, financial, logistical, policy and cultural barriers” to radiotherapy, including travel of hundreds of kilometres and wait times measured in months.6 Additionally, treatment, when obtained, often requires enormous out-of-pocket spending. Under such conditions, timely care becomes a privilege, when it should be a right.

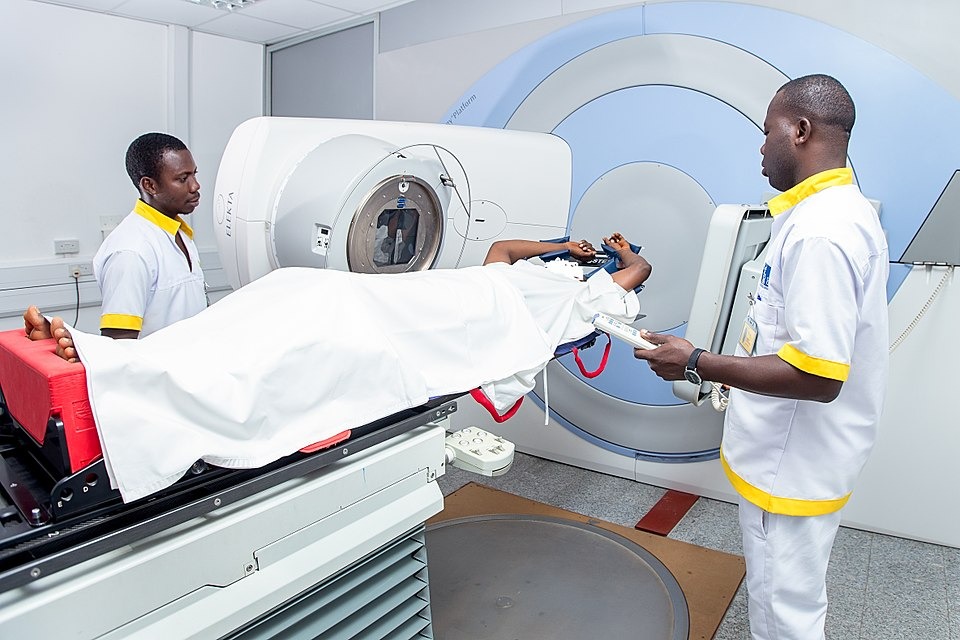

Radiotherapy infrastructure remains limited in much of sub-Saharan Africa—many countries have only a handful of machines or none at all. Shown here are Ghanaian radiotherapy technologists treating a cancer patient with a linear accelerator at one of West Africa’s leading oncology centres in Accra. This modern facility demonstrates ongoing efforts to improve cancer care capacity in the region. Photo by Chris Sam (Wiki Loves Africa 2017)

The Role of Culture and Silence

Compounding these structural issues are cultural and social dynamics that discourage early help-seeking. Prostate cancer symptoms (such as urinary difficulties or sexual dysfunction) may carry stigma or may be seen as an expected part of aging that men silently endure. Cultural norms around masculinity can make men reluctant to discuss prostate issues or to undergo procedures like a digital rectal exam. Ofori et al. note that men’s negative perceptions of screening, including fear and embarrassment, reduce engagement with care. In some communities, misinformation or fatalistic attitudes toward cancer further delay presentation.7

This silence is both systemic and cultural. When public-health campaigns omit men’s cancers and national strategies fail to allocate resources for screening, stigma becomes institutionalized. Prostate cancer, then, is not only a disease of the body but a symptom of structural neglect and social erasure—a malignancy sustained by silence.

The Right to Health: An Ethical and Political Imperative

The right to health, enshrined in international law, guarantees access to timely and appropriate healthcare for all. Yet for many African men, that right exists only on paper. When a curable disease becomes a death sentence due to the absence of affordable screening, functional equipment, or trained clinicians, the ethical dimension of global health is unrealized.

Global health funding has long prioritized infectious diseases such as HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis. While these initiatives have saved millions of lives, they have also contributed to an imbalance that sidelines non-communicable diseases. Cancer, one of the most fatal diseases in Africa, is often treated as an afterthought. Prostate cancer epitomizes this asymmetry. Addressing it demands the same political and moral urgency once directed at HIV/AIDS.

Toward Equity: A Path Forward

The disparities surrounding prostate cancer in Africa are not inevitable; they can be reversed with targeted, evidence-based interventions:

- Awareness and Education: Public-health campaigns must normalize men’s health discussions and address stigma. While evidence remains limited, culturally tailored outreach is widely recognized as a promising strategy to improve prostate cancer screening engagement across African settings.7

- Decentralized Screening: PSA testing and clinical evaluation should be integrated into primary-care systems, particularly in rural areas where medical infrastructure is sparse.

- Infrastructure and Workforce Development: As of 2010, only 23 of 52 African countries had any form of external beam radiotherapy, and the continent had a total of 277 machines—far below the International Atomic Energy Agency’s recommended coverage levels.5 Addressing this disparity includes not just increasing the number of radiotherapy machines, but also training radiation oncologists and medical physicists, expanding diagnostic capacity, and ensuring reliable maintenance and supply systems for existing infrastructure.

- Improving Access to Medicines: In the shorter term, improving access to available medications may offer substantial survival benefits. Abiraterone, a potent androgen-blocking therapy for advanced prostate cancer, has demonstrated improved outcomes in high-income settings. Although not yet widely accessible in sub-Saharan Africa, initiatives to promote its affordability—such as generic procurement and policy inclusion in essential medicines lists—could help bridge treatment gaps. Some treatment centers in the region have begun exploring options for offering abiraterone or chemotherapy when resources allow, but these efforts remain sporadic and underfunded.8

- Financial Protection: National health insurance schemes and donor programs must include cancer services to prevent catastrophic expenditures.

- Global Solidarity: International institutions should view cancer care as a human rights issue, not a mere luxury of development.

Closing the Gap

Prostate cancer in Africa is more than a disease—it is a mirror reflecting the entrenched disparities and priorities in global health. Every untreated case and every man lost to late-stage diagnosis is not just a medical failure, but a breach of moral responsibility. The disparity between what is medically possible and what is currently available for African men reveals a gap not of knowledge, but of will.

Closing this gap requires more than advanced treatments—it demands a global reckoning with how health is distributed, funded, and defended. Governments must build screening and treatment systems that prioritize early diagnosis and affordability. International partners must invest in oncology infrastructure as a human rights imperative, not a charitable gesture. And communities must be empowered with information to break the silence and stigma that surround men’s health.

Until detection and care are accessible, equitable, and embedded in public health strategies across the continent, prostate cancer will continue to expose the fragility of justice in global health. In this context, silence is complicity. Breaking that silence—through policy, funding, and collective advocacy—is not only the first step toward justice, but a declaration that African lives are equally worth saving.

——————————

References

- Bray, F., Parkin, D. M. & African Cancer Registry Network. Cancer in sub-Saharan Africa in 2020: a review of current estimates of the national burden, data gaps, and future needs. Lancet Oncol. 23, 719–728 (2022).

- Adeloye, D. et al. An Estimate of the Incidence of Prostate Cancer in Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PloS One 11, e0153496 (2016).

- Seraphin, T. P. et al. Rising Prostate Cancer Incidence in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Trend Analysis of Data from the African Cancer Registry Network. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. Publ. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. Cosponsored Am. Soc. Prev. Oncol. 30, 158–165 (2021).

- Seraphin, T. P. et al. Prostate cancer survival in sub-Saharan Africa by age, stage at diagnosis, and human development index: a population-based registry study. Cancer Causes Control CCC 32, 1001–1019 (2021).

- Abdel-Wahab, M. et al. Status of radiotherapy resources in Africa: an International Atomic Energy Agency analysis. Lancet Oncol. 14, e168-175 (2013).

- Ramashia, P. N., Nkosi, P. B. & Mbonane, T. P. Barriers to Radiotherapy Access in Sub-Saharan Africa for Patients with Cancer: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 21, 1597 (2024).

- Ofori, B., Fosu, K., Aikins, A. R. & Sarpong, K. A. N. The intersection of culture and prostate cancer care in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Afr. J. Urol. 31, 41 (2025).

- Kania, B. et al. Treatment approaches for prostate cancer in sub-Saharan Africa. Transl. Cancer Res.13, 6503–6510 (2024).