BY SOOAH PARK

Fans of the classic chick flick Mean Girls will be familiar with the sex education scene: “Don’t have sex, because you will get pregnant and die!”1 Though exaggerated for comedic effect, the global state of sex education is not far off. Less than one-third of adolescents from 155 countries surveyed by UNESCO reported learning helpful content during their sex education class.2 Access to quality sexual health education should also be considered a human right, regardless of cultural background or political ideology. However, access to stigma-free health information is limited, whether by culture, political polarization, or misinformation through social media. Ensuring universal access to sex education is not merely an educational issue; it is a matter of justice and human dignity that intersects with all aspects of an individual’s health.

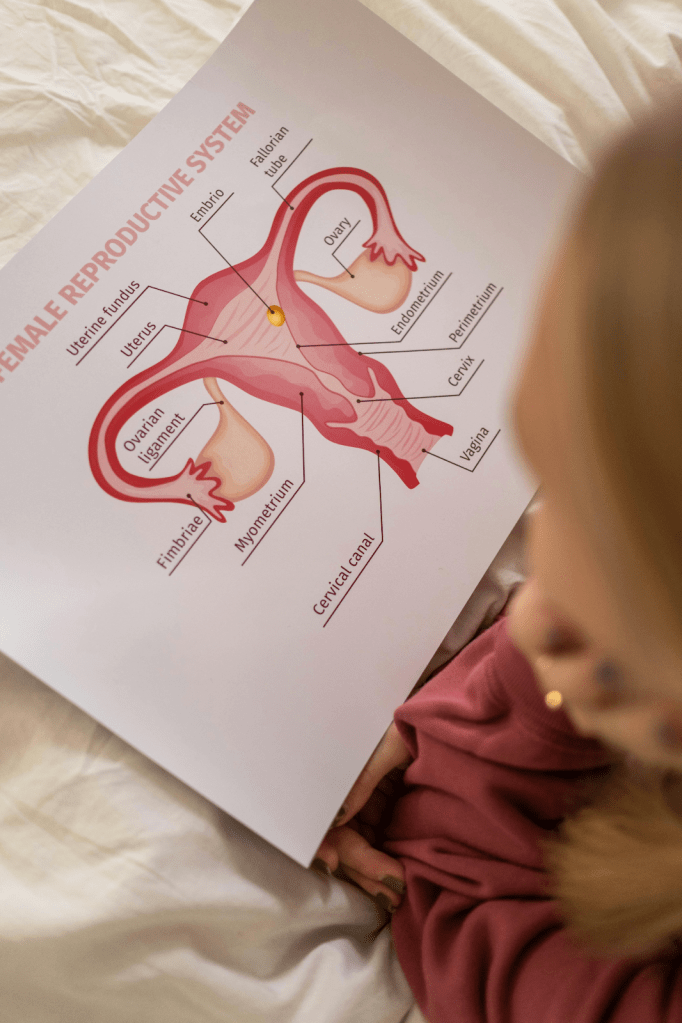

Comprehensive sex education (CSE) encompasses curricula that are age-appropriate, comprehensive, and culturally-appropriate. According to the World Health Organization, this includes family life education, relationships, consent, anatomy, puberty and menstruation, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs).3 United Nations’ Global Guidance recommends starting CSE at age five, beginning with how to identify and process emotions and respecting others.4 Additionally, CSE can improve adolescents’ abilities to react to sexual harassment and seek help, preparing adolescents to lead healthy lives without shame or fear. A common myth about CSE is its overly explicit nature and emphasis on sexual intercourse. Rather, CSE is focused on de-stigmatizing conversations about bodies, healthy relationships, and preparing older students to take care of their sexual health.1 For example, a sample CSE curriculum would provide instruction on different types of contraceptives, consent, and examples of setting boundaries in relationships.5

Opponents of CSE have frequently cited it as “sexualizing minors” and “promoting sexual behaviors.”6 However, abstinence-only education, which is sex education that stresses abstinence from sexual intercourse until marriage, produces greater negative effects. Abstinence-only curricula increase intercourse without condoms, contribute to teen pregnancy rates in the United States, and increase rates of STIs.7 Lack of CSE also fosters harmful gender-based discrimination, violence, and disproportionately high rates of STIs among women and sexual minorities.8 Reducing these disparities and offering all adolescents equal opportunities in life begins with stigma-free education.

CSE is unfortunately still lacking in countless countries across the world, albeit in different ways. To better understand how sex education policies take shape across different countries, I will examine sex education in the United States and South Korea.

In the United States, parental influence and political polarization perpetuate inequalities in sex education. Sex education curricula vary heavily across states, with only 27 states and Washington, D.C. requiring sex education to be taught in public schools.4 However, these disparities persist across school districts, depending on parental input and available educational funding. Growing up in a Chicago suburb, I remember our teachers splitting our fifth-grade class into boy and girl classrooms for health class, reminding us not to tell others what we learned. In the school district 15 minutes away, my friends received no form of sex education until high school. Moreover, CSE has been heavily politicized and continues to present significant barriers in the U.S. education system, representing tension between parents, teachers, and policymakers who believe they know what is best for students. Yet, at the end of the day, the push against CSE in the U.S. is driven by political ideology and personal values, not by consideration for growing adolescents.

Recognizing these political schisms, I strived to expand CSE. In high school, I connected with high school students in South Korea to help them develop new curricula. However, South Korea faces markedly different issues and needs for sex education for cultural and political reasons. Schools emphasize reproductive concepts and normative family models in response to concerns about the nation’s extremely low fertility rate.9 South Korean curricula tend to ignore birth control, consent, and sexual orientation or gender identity, influenced by cultural taboos.10 However, the provision of sex education is relatively standardized and consistent across the country compared to the U.S. Students receive at least some form of sex education from their health teachers or a school nurse during primary and secondary school.10 Although South Korea has very low teen pregnancy and STI/HIV rates, open conversations regarding bodily autonomy, sexual health, and even traditional gender roles are sidelined.11

The future of sex education depends on our willingness to recognize it not only as a public health priority but as a fundamental human right. Governments, policymakers, and educational institutions must take a more active role in implementing standardized and comprehensive curricula that go beyond biological explanations. Above all, these frameworks must be sensitive to local cultural values rather than imposing Western norms of sexuality. As our youth navigate the complexities of adolescence, access to non-stigmatizing information is not a privilege; it is a right that every society should strive to uphold.

——————————

References

1. Waters, M. (Director). Mean Girls. (Paramount Pictures, 2004).

2. Sohee, L.-M. Gender-Sensitive Sex Education for the Youth in Korea. Asian Journal of Women’s Studies 20, 173–184 (2014).

3. Ryu, H. & Pratt, W. Reducing the Stigma of Sexual and Reproductive Health Care Through Supportive and Protected Online Communities. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2024, 970–979 (2025).

4. Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS). SIECUS State Profiles. Available at: https://siecus.org/siecus-state-profiles/ (Accessed: 25th November 2025).

5. Goldfarb, E. S. & Lieberman, L. D. Three Decades of Research: The Case for Comprehensive Sex Education. J. Adolesc. Health 68, 13–27 (2021).

6. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Comprehensive Sexuality Education. Available at: https://www.unesco.org/en/health-education/cse (Accessed: 25th November 2025).

7. World Health Organization (WHO). Comprehensive sexuality education. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/comprehensive-sexuality-education (Accessed: 25th November 2025).

8. UNESCO et al. The Journey towards Comprehensive Sexuality Education: Global Status Report. (UNESCO, 2021). doi:10.54675/NFEK1277.

9. Stanger-Hall, K. F. & Hall, D. W. Abstinence-Only Education and Teen Pregnancy Rates: Why We Need Comprehensive Sex Education in the U.S. PLoS One 6, e24658 (2011).

10. Nho, J.-H. The evolvement of sexual and reproductive health policies in Korea. Korean J. Women Health Nurs. 27, 272–274 (2021).

11. Lameiras-Fernández, M. et al. Sex Education in the Spotlight: What Is Working? Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 2555 (2021).