Exploring how epistemic injustice marginalizes local expertise in authorship, policy, and research, shaping whose knowledge counts in global health

BY OYINKANSOLA ADEBOMOJO

It was late December 2013 in Guéckédou, Guinea, a time that should have been festive and filled with celebration. Instead, local clinicians felt a growing sense of dread. Patients were arriving with severe fever, rampant vomiting, and blood beneath the skin. It was an unexplainable pattern of hemorrhagic fever cases. By January 2014, Guinean health officials and field teams from Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), the French name for Doctors Without Borders, began to suspect an outbreak of Ebola. MSF and local officials quickly alerted national authorities and international partners, including the World Health Organization (WHO).

As the call was ignored, the situation got worse. Treatment centers became overwhelmed as both governments and international communities were slow to respond. By March 2014, these symptoms of hemorrhagic fever had spread through southeastern Guinea into Liberia and Sierra Leone. On March 12, 2014, an MSF Team in Guinea collected blood samples and sent them to laboratories in Lyon, France, and Hamburg, Germany to confirm what many had thought.3 Only after the European laboratories confirmed the results did WHO issue its first official statement acknowledging the Ebola outbreak in Guinea.1 In its March 2015 report, Ebola: Pushed to the Limit and Beyond, MSF wrote: “Despite repeated calls by MSF for massive mobilization of resources and personnel, the international response was slow, uncoordinated, and ineffective.” MSF further emphasized that they had been treating patients for months before WHO and donors scaled up.1

This dynamic between local African health workers, researchers, and international health systems is not new. In 1976, Congolese physician Jean‑Jacques Muyembe-Tamfum was the first to collect blood samples from patients in Yambuku, identifying what became known as Ebola.4,5 Yet credit for the discovery went largely to Belgian scientist Peter Piot and his team, leaving Muyembe’s role sidelined for decades.4

Both of these events—the discovery of the Ebola virus and the identification of the Ebola outbreak in Guinea—demonstrate a recurring pattern of “epistemic injustice,” a term coined by Miranda Fricker, which refers to when someone’s knowledge is ignored or undervalued because of who they are.6 In these cases, African doctors and researchers’ opinions were treated as less credible, and their expertise was discounted until Western institutions validated their findings.

WHO later admitted that “factors unique to West Africa helped the virus stay hidden and elude containment measures,” acknowledging that cultural practices and governance realities complicated its existing response frameworks.2 This reveals a deeper systemic issue within global health frameworks, originating from colonial ties.

Despite global health’s pledge of universality and health for all, the field routinely privileges Western knowledge and frameworks.7 It structurally commits epistemic injustice by excluding marginalized scholars from producing recognized knowledge and by ignoring cultural interpretations in policy. These epistemic wrongs violate the fundamental human right to health, which depends on participation, accessibility, and acceptability. By WHO’s own definition, a human-rights-based approach to health requires participation, empowering communities to shape health decisions; equity, prioritizing those furthest behind and addressing intersecting discrimination; accountability, ensuring transparent, enforceable obligations from institutions; and cultural acceptability, guaranteeing care that is people-centered, respectful, and responsive to local values.8 Yet epistemic injustice in global health—through exclusion from authorship, interpretive erasure, and the dominance of Western epistemologies—violates each one of these principles, turning the right to health into a conditional privilege.

Global health begins at research, where scientific inquiry translates into helping people. This begs the question: who gets to produce the knowledge and whose work is deemed credible?

Global collaboration is very important, especially with the recent example of the COVID-19 pandemic. Rapid collaboration in research and interventions help foster more significant responses to rapid global changes by enabling international research, decreasing biases, and increasing study validity while managing overall research time and costs. In academia, authorship, particularly first and last authors, are key positions for intellectual leadership that help with academic promotion as well as gaining funding from grants.

However, across multiple large-scale analyses, authorship data reveal a consistent pattern of authorship imbalances and unequal partnerships in global health research. In a review of more than 7,100 studies based in sub-Saharan Africa, only 52.9% of first authors and 54% of all authors were from the country of study, dropping to 23% when collaborators were affiliated with elite U.S. or European institutions.9 A similar pattern appears at the institutional level: among 5,805 UCSF-affiliated articles on African health research, just 16.3% of first and 14.1% of last authors were from low-or lower-middle-income countries, while over 70% came from high-income institutions.10 Comparable disparities of underrepresentation of authorship of researchers from Low-Income-Countries (LICs) and Low-and-Middle-Income-Countries (LMICs) are seen amongst medical specialities of family-medicine journals, reproductive-health collaboratives, and surgical and clinical research, where they typically hold data-collection roles rather than principal authorship, with women in LMICs doubly underrepresented.11–14 These trends underscore epistemic injustice within academia, where LMIC researchers are not empowered to define research agendas.

A LMIC-originated early-career male researcher in the field of WASH (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene), when asked about inequitable distribution of authorship and acknowledgement between global research collaborations with HICs, stated: “Authorship is that sort of thing whereby you take the heavy lifting and then at the end, they end up saying this one is going to be their first author. And the question is, why would they be the first author? I did the heavy lifting on this one.”15

Additionally, there are no accountability systems for epistemic harms when local researchers are excluded from authorship or data ownership, where the contributions of LMIC researchers can be undervalued or erased with no institutional recourse. An LMIC-originated late-career female researcher in the field of WASH shared:

We had that terrible experience where one of the partners actually solely wrote an article with her name alone on it. [We contributed to the] paper by data collection, answering many questions, giving writing reports, and then this person turns out to write a paper on her own… [This] set a terrible precedent.15

These disparities exemplify testimonial injustice, which Fricker defines as when prejudice causes a listener to give a lower level of credibility to the speaker’s word.6 Institutional norms and implicit biases discredit LMIC scholars as credible producers of scientific knowledge. This is caused by structural drivers like language, cost barriers, editorial bias, and funding inequities. A 2023 review of LMIC investigators identified restricted access to high-impact journals, editorial bias against non-native English writing, and limited training in technical English as primary barriers.16 Globally renowned journals mainly publish in English, producing a monolingual filter that privileges Western researchers with strong English language proficiency and stifles a talented scientist’s potential when ideas are judged by language fluency rather than scientific merit.19 A global bibliometric analysis of 786,779 publications confirmed these patterns: even in studies based in LMICs, only 36.8% had an LMIC first author and 29.1% an LMIC last author, while 86% of all global health articles were published in English.18 This is exacerbated when journals like JAMA Network Open report that 95% of editorial staff are based in HICs, and BMC Medical Ethics lists no editors from low-income countries. Editorial bias and peer review inequity within global health manuscripts from non-native English speakers face higher rejection rates, not for scientific flaws, but for linguistic presentation.17, 19, 20 An LMIC-originated early-career female researcher in the field of WASH said:

You really need to work extra to prove what you can do because there’s this kind of stereotyping… because someone [who] feels English is not your first language has already placed you at a level you cannot match up to… You really need to prove who you are. [You] really need to work extra hard.15

Geographic distribution of a) all authors, b) first authors, and c) last authors in publications on decolonizing global health and global health partnerships. © Chris Rees, Gouri Rajesh, Hussein Manji, et al., 2023. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

If editorial boards of globally renowned journals are dominated by HIC actors, which inherently equate quality knowledge with Western credentials and English fluency, then submission patterns and review decisions will systematically advantage HIC researchers. The lack of LMIC perspectives on shaping editorial decisions demonstrates despite global health’s claim to promote health equity through participation, it structurally discriminates against knowledge production from LMIC researchers. Additionally, funding inequities channel resources through Western institutions, as LMIC researchers must often partner with HICs merely to be grant-eligible.15 This creates a system of familiarity that rewards institutional Western prestige over scientific relevance or creative innovation. As a result, knowledge creation becomes linguistically and institutionally westernized: LMIC scholars are relegated to roles of “data collectors rather than thinkers.”17 This is a form of epistemic injustice by silencing the very voices essential for developing culturally grounded, context-responsive health solutions. Excluding LMIC researchers from authorship, leadership, and funding reproduces colonial hierarchies in science, thus violating the equality of participation in knowledge creation WHO claims to value.

Epistemic injustice is not only in who produces knowledge but in how knowledge is interpreted and valued. Interpretive exclusion, coined by Adebisi, occurs when global and national health systems privilege Western biomedical frameworks while marginalizing the lived, contextual, and cultural understandings of health in LMICs.17 This exclusion is visible in WHO’s own epidemic governance, where decision-making boards such as the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE) and the Strategic & Technical Advisory Group on Infectious Hazards (STAG-IH) remain dominated by members from HICs. When looking at SAGE and mapping each member’s country of institutional affiliation to the World Bank Income List, out of the 15 members on the board, 46.7% of members are from high-income countries, 26.7% from upper-middle-income countries, 20.0% from lower-middle-income countries, and none from a low-income country. A similar trend is present among STAG-IH members, with 60% of the 20 members coming from high-income countries, 25% from lower-middle-income countries, and 15% from upper-middle-income countries, and none from a low-income country.21–23 This is despite the great immunization gaps and epidemic burdens that exist in Africa, South Asia, and Latin America.24,25

The WHO’s science council, in charge of guidance on scientific and technological innovation, acting as the “voice of scientific leadership,” is composed of 10 members, of which 40% are from upper-middle-income countries, 30% from high-income countries, and 30% from low-middle-income countries.21, 26 In all these councils, there is a dominance of members from high-income countries and upper-middle-income countries, with no representation of low-income countries and lower representation of lower-middle-income countries. There is no voice to advocate for the interests and agendas of LIC and LMIC researchers and communities, thus violating the principle of engagement, as these communities are not engaged and represented thoroughly within these advisory boards.

As a result, these structural imbalances bleed into policies that fail to reflect local priorities or explanatory models of illness. The WHO’s own reviews of past outbreaks highlight the pitfalls of ignoring local models, such as when the WHO’s burial and containment guidance conflicted with community traditions during the Ebola outbreak. In its analysis of the 2014-2016 West African Ebola epidemic, the WHO revealed that “when technical interventions cross purposes with entrenched cultural practices, culture always wins,” and concedes that “control efforts must work within the culture, not against it.”27 While WHO identified the problem that interventions clashed with social norms, it struggled to translate that insight into structurally embedded solutions. Most adaptations, like the “safe and dignified burials,” were implemented only after months of resistance and thousands of deaths.1, 27

Despite this, during the COVID-19 pandemic, global attention initially followed HIC priorities with “attention to coronavirus in Africa… [as] secondary to the focus on China, Italy, and the United States,” demonstrating how Western donors’ frameworks and governance overshadowed the needs of various African countries during the pandemic.28 With the emergence of African “epistemic communities” that blended indigenous practices with medical science, Africa’s CDC emphasized advanced community-based, context-sensitive strategies instead of following WHO or Western donor metrics of surveillance and case reporting.28 Senegal’s mobile labs increased testing capacity within 24-hour results, while Liberia implemented airport screenings and aggressive contact tracing immediately after the WHO declared a pandemic, and later used community-based contact tracers. The continental response from the Africa CDC and the African Union distributed millions of test kits and established regional knowledge hubs. These Africa-led initiatives reflected “Africa-based solutions that resonate with local populations,” demonstrating that culturally grounded governance can outperform Western frameworks.28

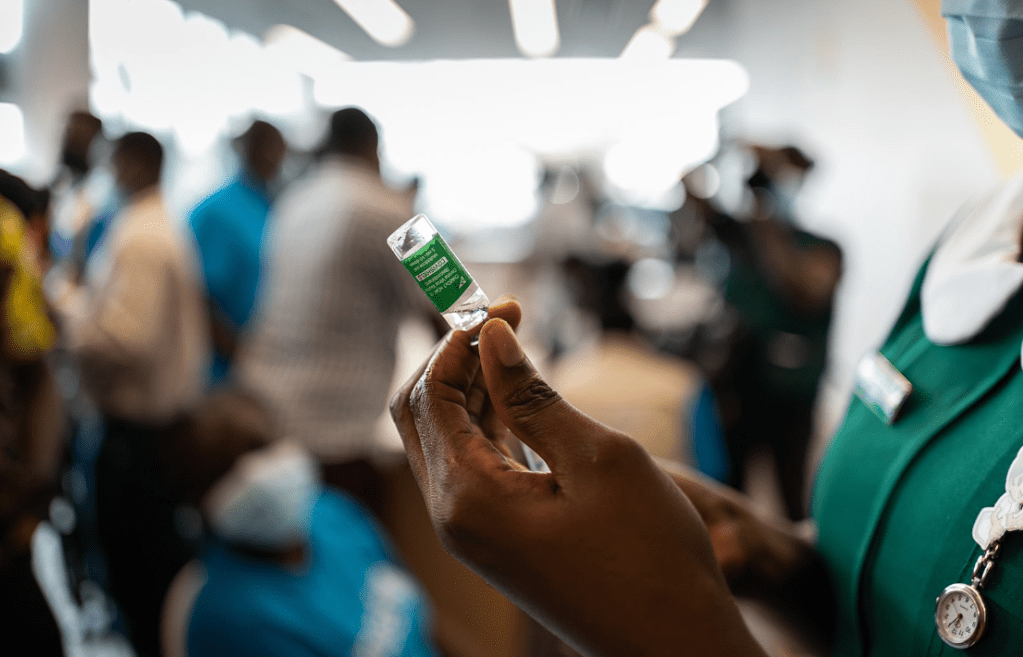

Nurse prepares to administer the AstraZeneca/Oxford COVID‑19 vaccine at Ridge Hospital, Accra, Ghana, 2 March 2021. © World Health Organization / Nana Kofi Acquah.

Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution‑ShareAlike 3.0 IGO.

If the right to health means dignity, participation, and inclusion, then epistemic injustice must be recognized as a human rights violation. It began in Guéckédou, when the local doctor’s warning went unheard until it was echoed by a Western voice.

This silence, this failure to listen, is not incidental. It is structural.

Elizabeth Anderson’s conception of epistemic justice reminds us that justice in knowledge is not an individual virtue but an institutional one.29 Global health systems, from the WHO to academic publishing, are built upon hierarchies that determine whose knowledge is credible and whose is dismissed. These hierarchies are not merely academic injustices; they are violations of human rights. Article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights recognizes the “highest attainable standard of health” as a right.7 Yet that standard is impossible without fair participation in knowledge production. The WHO’s own Constitution affirms health as a “fundamental human right,” and that right cannot be realized when decision-making remains monopolized by high-income institutions.8

Achieving health equity requires epistemic equity through diversifying WHO boards, funding multilingual publication platforms, valuing indigenous, community, and local knowledge, and institutional accountability in promoting equitable research partnerships and changing academic promotion criteria to reward fair authorship practices. Health inequity begins with knowledge inequity. The right to health will never be attained until global health systems protect not only the right to treatment but the right to speak, to be heard, and to be believed.

——————————

References:

2. World Health Organization (WHO). https://www.who.int.

8. Human rights. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/human-rights-and-health.

24. Global Burden of Disease (GBD). https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/gbd.

26. Science Council. https://www.who.int/groups/science-council.